- Home

- Alison Irvine

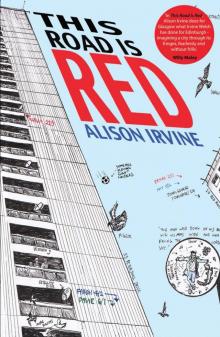

This Road is Red

This Road is Red Read online

ALISON IRVINE was born in London to Antipodean parents. She was brought up in London and Essex and moved to Glasgow in 2005 to study an MLitt in Creative Writing at Glasgow University. She graduated with distinction in 2006 and since then her writing has been published in a variety of magazines and in an anthology of Glasgow writing, Outside of a Dog. In 2007 she was awarded a Scottish Arts Council New Writer’s Bursary. This Road is Red is her first novel and was developed through her close association with Glasgow Life’s Red Road Flats Cultural Project.

She lives in Glasgow with her family.

Alison Irvine’s This Road is Red is a first novel. It’s worth stating this because, as the cover of her book tells us, ‘The Characters are Fictional … Red Road is Real’. The novel is based around Glasgow’s Red Road Flats, the massive tower blocks in the north-east of the city which progressed from a hope for a bold new future, to scenes of urban deprivation and violence, and to ongoing demolition plans.

The novel was written in collaboration with Glasgow Life’s Red Road Flats Cultural Project, using inhabitants’ oral histories as a research base. The resulting novel is so much more than a research project, though: it is both richly imagined and deeply rooted.

It opens with a vignette from the 1960s, of one of the builders working on the ‘mud and cabbage fields’ that would become Red Road, and closes with the concierges who watch over the emptying flats in 2010. In between, we are introduced to a range of sparky voices from the successive generations who lived in the flats, including waves of immigrants. We meet teenage boys who sneak out at night, tights over their heads, to paint lines for a tennis court;

a kestrel kept on a balcony; the lofty views westwards to Arran from the highest flats; a long-time inhabitant leaving in his coffin. This is a spirited, funny and moving novel, and a wonderfully human testament to the community from which it developed. CLAIRE SQUIRES

The flats inspired many works of art, but it is, perhaps, Alison Irvine’s This Road is Red, drawn from interviews with former residents, that best captures their ambivalence. The flats were a source of pride and embarrassment, a place of fierce friendships and bitter feuding, a sanctuary and a prison. In four decades, they saw lives transformed and lives destroyed.

DANI GARAVELLI, The Scotsman

Irvine’s stories are by turns sad, frightening, moving, dark, occasionally wickedly funny and always compelling. MORNING STAR

This is a beautifully written tale of life in a high-rise housing scheme. The author spent a year interviewing past and present residents and crafted their real-life stories into a collection that tells how the last five decades have impacted on the community.

The Red Road flats have long been an iconic Clydeside landmark. The scheme was conceived by the council as a solution to Glasgow’s overcrowded slums. Red Road seemed to herald a bright future. But like many schemes of the time, poor-planning and cost-cutting meant no community facilities, few amenities and major maintenance problems. While parts of Glasgow prospered,

Red Road was ignored. Today Red Road is notorious for poverty, crime, drug abuse and vandalism.

The most moving stories are about the plight of refugees. A year ago Red Road hit the headlines when a family of Russian asylum seekers facing deportation jumped to their deaths from the tower block.

That evening 400 local people joined a commemoration at the spot where the three died. It wasn’t Red Road’s first suicide but the tragedy shone a light on the plight of many refugees and the terrible housing conditions in the poorest parts of Glasgow.

Alison Irvine’s first book is a fine tribute to the people of the Red Road and a great account of how human solidarity can prevail in even the bleakest circumstances.

JONATHAN NEALE, Socialist Review

This Road is Red

ALISON IRVINE

Luath Press Limited EDINBURGH

www.luath.co.uk

First published 2011

This edition 2015

ISBN (EBK): 978-1-910324-62-2

ISBN (BK): 978-1-910021-53-8

Published by Luath Press in association with

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

© Alison Irvine 2015

For Eddie

A Word from the Red Road Flats Cultural Project

Glasgow Housing Association (GHA) and Glasgow Life created a partnership in 2008 to develop and deliver a range of historical and art programmes for current and former residents of Red Road and the surrounding neighbourhoods to commemorate the end of an era in Glasgow’s history.

As much of Red Road’s significance is attributed to its size, the programmes undertaken have focused on people’s memories, stories and photographs.

The aim of the project is to capture the full story of Red Road’s fifty-year life. We hope this book will help keep Red Road alive for years to come.

Details of the full range of projects which have been delivered and are in progress are available at www.redroadflats.org.uk.

In memory of John McNally, resident of the Red Road Flats 1969–2009

Acknowledgements

THE BOOK WOULD NOT have been possible without the generosity of the people I interviewed. Their time, their enthusiasm for the project and their willingness to go over the tiny details of their experiences gave me such rich material to work with. Thank you so much. You have made writing this book an absolute pleasure:

Beki

June Aird Matt Barr Mojgan Behkar Jim Bonner Louise Christie Sara Farrukh

Jahanzeb Farrukh Derek Fowler Ruvinbo Gombedza Aysha Iqbal

Azam Khan Veronica Low Willy Maley Jim McAveety

Helen McDermott Sharon McDermott Billy McDonald Peter McDonald Jean McGeough Finlay McKay

John McNally

Frank Miller

Ntombi Ngwenya Bob Niven Thomas Plunkett Marie Quinn Grant Richmond Donna Taylor

Iseult Timmermans

And the young people from Impact Arts’ Gallery 37: Ibrahim, Christian, Heder, Rahel, Ibrahim and James.

Thank you also to Bash Khan, Johnny McBrier, James Muir, Lindsay Perth, Remzije Sherifi, Eulalia Stewart, Kate Tough, Impact Arts, the Scottish Refugee Council, members of the Red Road Flats Project Steering Group, and Glasgow Life’s Martin Wright, Ruth Wright and the rest of the team. Thanks to Glasgow Housing Association for funding the project. Particular thanks to Jonny Howes from Glasgow Life whose support has been invaluable.

Thank you to Gavin MacDougall, Christine Wilson and their colleagues at Luath Press, and to Mitch Miller who illustrated the book.

Lastly, thank you to all my family: especially to Linda, Luke and Sammy Byrne, and of course to Arlene and Isla. To Eddie, thank you for everything. I couldn’t have done this without you.

Foreword:

This Book Must Be Read

WILLY MALEY

GLASGOW PRIDES ITSELF on the splendor of its built environment. Being uk City of Architecture in 1999 gave it a chance to preen. Yet as recently as 2011, award-winning architect Malcolm Fraser launched a blistering attack on the civic vandalism and economic short-termism that continues to blight Glasgow’s urban landscape (‘Wrecks and the city’, Sunday Herald, 10 April 2011). Fraser’s remarks were especially damning regarding the demo- lition or dereliction of schools in a city with a rich tradition of transforming lives through teaching. I must be one of many working-class Glaswegians empowered by education who can only point to a piece of wasteground now and say, ‘That’s where my life was turned around’. Both my primary and secondary schools have been reduced to rubble, a world of memories flattened by the wrecking ball. This, as Fraser persuasively argues, is the demolition of democracy

. I had never grasped the economics of such school bulldozing – the ultimate in bullying – until I read Fraser’s excellent account of the shenanigans involved.

The Commonwealth Games offer another opportunity for Glasgow to strut its stuff, and the announcement on 3 April 2014 that five of the six remaining high-rise blocks at Red Road would be flattened as part of the opening ceremony was quite in keeping with the chronic disrespect for local communities that is part of a familiar narrative. Glasgow City Council leader Gordon Matheson commented at the time: ‘We are going to wow the world, with the demolition of the Red Road flats set to play a starring role. Red Road has an iconic place in Glasgow’s history, having been home to thousands of families and dominating the city’s skyline for decades. Their demolition will all but mark the end of high-rise living in the area and is symbolic of the changing face of Glasgow, not least in terms of our preparations for the Games’. Despite such enthusiasm, the decision to demolish Red Road as part of a media circus was seen as a red rag and met by an upwelling of outrage.

Eleven days later the wow factor had faded and the decision to blow up the flats as a spectacular fireworks display was aban- doned. Three days after this U-turn was announced another newspaper report stated that Glasgow has the lowest life expectancy in the uk. In fact, life expectancy in Glasgow’s East End is among the lowest in Europe. To be honest, we haven’t moved on from the debates of twenty-five years ago around Workers City versus Saatchi and Saatchi makeover. Cosmetic campaigns from ‘Glasgow’s Miles Better’ to ‘Scotland with style’ ignore the substance abuse, the inequalities and social segregation of the city, and the lack of any real ‘commonweal’, or wealth in common.

In Alasdair Gray’s Lanark (1981), Duncan Thaw remarks

that nobody notices Glasgow, ‘Because nobody imagines living there’. Thaw asserts that ‘if a city hasn’t been used by an artist not even the inhabitants live there imaginatively’, and he asks:

What is Glasgow to most of us? A house, the place we work, a football park or golf course, some pubs and connecting streets … Imaginatively Glasgow exists as a music-hall song and a few bad novels. That’s all we’ve given to the world outside. It’s all we’ve given to ourselves. (Gray, Lanark, p. 243)

In literary terms, Glasgow has come a long way since Lanark, and Alasdair Gray has done more than most to conjure the city into being as an artistic entity. Having said that, Glasgow also exists imaginatively, and always has done, in the lives and minds of the city’s walkers, watchers, and workers, so we shouldn’t be so hasty to dismiss popular culture and local experience.

Scottish writers have tried, through criticism, memoirs and

novels, to fill the gap site identified by Gray – one thinks here of Glasgow: Going for a Song (1990) by Sean Damer, Imagine a City: Glasgow in Fiction (1998) by Moira Burgess, and Our Fathers (1999) by Andrew O’Hagan. In This Road is Red, Alison Irvine imagines a city, a scheme in the sky, the Red Road flats. When my father died in April 2007 – he was 99 years old, but it still came as a great shock – I looked out of the eighth-floor window of the Western Infirmary at the city lights and thought of the town whose streets he had walked for nearly a century, the places he’d lived, from the Calton to Shettleston to Barlanark to Possil and Maryhill, and the places he’d laboured, helped build or maintain: Parkhead Forge, the rail- way lines at Cowlairs, and the Red Road flats, on which he worked as a labourer when those great fingers of concrete and steel first started to reach for the sky in the mid-1960s. He was older then than I am now, in his late fifties and early sixties, but still working away, still telling stories, like the one about watching the final of the European Cup on 25 May 1967 by standing with other men staring through the window of a television shop in Springburn Road on his way home from the Red Road. I was scared of heights as a boy, so just listening to my father’s talk of going up in ‘the hoist’ made me dizzy.

Alison Irvine has listened to the stories of others, ordinary people with extraordinary tales to tell. That makes her a real writer. I never taught Alison, though she was a student on the Creative Writing course at Glasgow University, so I can’t take any credit, try as I might, but I was lucky enough to read a typescript of This Road Is Red in advance of publication and I thought it was one of the most important books about Glasgow and urban life I had read in a very long time. It offers an insight into city life that few Scottish novels can emulate. Although Irvine Welsh’s Glue did chart the development of hopes and dreams through housing schemes, Trainspotting never managed to imagine a city in quite the way Alison Irvine

does in This Road is Red, while James Kelman’s best book, The Busconductor Hines (1984), has little to say about ‘the District of D’ – Drumchapel – and focuses instead on a single individ- ual, and on places of the mind.

F. Scott Fitzgerald has his narrator Nick Carraway say in an ironic epigraph to The Great Gatsby, ‘life is much more successfully looked at from a single window’, but too often our authors take this at face value and fail to give us crowd scenes or communal perspectives. For the workers who raised the Red Road and for its early inhabitants it was a green light, a Yellowbrick Road into the future. That it proved a relatively short-lived experiment in urban living makes it an important archive of memories to be preserved and lessons to be learned. The fact that a block of the Red Road flats is still occupied by asylum seekers, in a city with the lowest life expectancy in the uk, and a poor record of housing its immigrant communities, is a reminder that poverty can’t be obliterated by high explosives any more than it can be glossed over by shoddy publicity campaigns or corporate makeovers and takeovers. The first residents of the flats were also seeking asylum, getting out of Glasgow’s ghettos.

This Road is Red is a kind of model of multi-storey narration as opposed to self-absorbed curtain twitching. I have never understood why so many working-class authors write in a detached manner as though they lived in bungalows. Where writers like Kelman and Gray give us individual consciousness, single windows through which to view the world, Alison Irvine has a gift for bringing whole communities to life, a keen eye for the buzz of life, and a highly developed sense of history and memory across generations. I’m delighted that This Road is Red is being reprinted. It is well worth reading. Capturing a community in all its richness and diversity and with such compassion and insight really is a towering achievement.

Prologue

1964–1969

A MAN WITH A strong back and muscles thumbs braces over his shoulders, then sits to tie black boots. He stands at the sink and drinks tea with milk and sugar. Tunes the radio to fiddle music. Butters bread, cuts cheese and makes his piece. Finds his silver piece tin and puts his piece inside. Pours boiling water over tea leaves in a flask. Combs Bay Rum through his hair.

A pile of library books on the table. A basin under the table for later, to steep his feet. His wakening household. Children; nine of them, shifting in their shared beds. A son, the youngest, waiting at the kitchen door to make his breakfast and retune the radio. Bunnet. Coat. Piece tin and flask. Out the door. His son takes over the kitchen.

The man walks to Red Road. Mud and cabbage fields. Wet and wind and rain. The steel hanging off cranes. The gangs assembling. A day’s work. Years’ work. For him and for the trades. Good money.

Eating his piece and a young one sits next to him, tells him he’s not happy because he’s working overtime and not getting as much as his pal in another gang. You’ll get your bonus, don’t fash, the man says and takes it upon himself to have a word with the ganger.

Every day, the walk in his hard boots through Possil to Red Road. The steel frame rising, fixed at the joints by men with balance and nerve. The man going up in a hoist. Using muscles honed laying sleepers at Cowlairs. Hup hup hup. They get their bonus.

Twenty floors up. Someone lights a fire to fend off the

freezing cold. Someone else tells him to put it out or they’ll all get sent down the road. Men not expecting their legs to sway with fear,

looking down at the mud and the kit and the huts.

The man sees Arran on the clearest day yet. Its blue-grey bulk at the far side of the sky. The Clyde and the shipyards. Grit and glitter. It’s shipyard steel they’re building with. Sand and gold on the Campsie Fells. The men stop work to look, take bunnets off and wipe foreheads.

In summer eight students and their teacher come from Barmulloch College, go up in the hoist, learn about sway in tall buildings. Hold a plumb line and see that the steel structure sways. Can’t feel it but see the line move so believe it. The man feels it when they clad the steel, and the wind bullies the blocks, unable to get through anymore. Oh, then they sway.

More disputes. The men hear of another gang on more over- time. They’re not trades, he and these men, they’re the lowest paid and he will not have them exploited. He’s a union man, a fighter for the left. Don’t fash he says to the young ones.

They stop work for the opening of Ten Red Road. Thirty floors of four-room apartments. Ceremonies, plaudits, photographs. Ballots and excitement. Firemen doubling up as removal men and pulling up with people’s furniture.

Then on with Thirty-three Petershill Drive. Newspapers tell of overspend and high costs. It’s work though, for locals and those who move into the area, turning up with skills and strength. Working six or seven days a week, like the man, for his wife and his weans.

Late May 1967 and the boy waits for his father. The street is empty of boys and footballs. Everyone’s inside. The man works overtime and checks his watch. He’s too high up to hear cheers or roars from television sets. It’s on his mind as he works. They stop in time to run to Springburn and stand outside Rediffusion. Black and white televisions in the window show the match in Lisbon. He stands with other labourers and they

This Road is Red

This Road is Red