- Home

- Alison Irvine

This Road is Red Page 2

This Road is Red Read online

Page 2

watch the second half from the pavement, looking in at the televisions. At the final whistle their arms raise above their heads and the man sees the smiles of the fans in the crowd and the smiles of the players and their own smiles reflected in the shop’s window. Come for a drink, his workmates say, and he says no, he doesn’t care to drink anymore and he walks home happy. He finds his boy celebrating out the back and stands among triumphant neighbours watching wee ones go wild.

His wash at the sink is pleasurable and slow. Champions. All day labouring, all day thinking about the game. He pours water from the kettle into the basin, tops it up with cold. Moves a chair. Sits. His boy watches as he unlaces his hard boots and rolls each sock down an ankle and foot. He puts his feet in the basin and the boy tunes the radio to Sanderson and Crampsey. A plate of food, kept warm, a quick sleep and the next day is work and some of the boys are tired from celebrating.

The man is sixty years old. He labours on all the buildings. Is there till the last in 1969. He builds the concrete castle for the weans and the paths that go from building to building. Low walls. Grass. A place where the shops will be. Full classes and overspills in the primary schools. More schools needing built. The last of the trades come in to do their jobs. Tenants move in and the workers move out. Red Road. He built the highest towers in Europe.

His son views the flats as he walks with his siblings in a line behind his father and he thinks of the Yellow Brick Road. Likes them. Sleek. Space age. Mammoth. Rid Road says his mother. Red Road. His father’s last workplace. Red Road. Houses for thousands.

Section One

May 1966

SHE WATCHED AS THE towers grew larger. Her boy played with the frayed seat-top in front of him. The bus slowed at every stop and people took an age to get on and off. She would cry, she swore, if they’d run out of houses and she had to go back to the Calton.

The buildings were shocking. Massive. Some finished, with sleek sides and neat rows of windows, others with their insides exposed, dark as engines. Half-finished cladding. Cranes hanging over the tops. Scaffolding. The noise of the construction was exhilarating.

‘Ma, Ma, look up, they’re falling!’

May pulled her son’s arm and told him they didn’t have time to stop but she glanced at the tumbling clouds at the tops of the towers and knew what he meant.

It seemed like the whole of Glasgow was in the foyer of one-eight-three Petershill Drive. Shouts and laughter and hand claps.

‘Are they nice?’ May said to someone, anyone.

‘Brand new.’

‘What did you get?’

‘Twenty-two floor. Number four.’ The woman’s face was full and freckled. She smiled.

Her man dangled a key from his thumb and forefinger then snapped his fist around it. He wore a suit. His smile was huge.

‘It’s something else.’ The woman touched May on the shoulder. ‘The most beautiful house I’ve ever seen.’

‘Come on, son.’

May didn’t care what she got but she had to get something. The man at the desk sat like Santa. He clicked a pen with his thumb.

‘What do I do?’

‘Put your hand in and take a piece of paper.’

‘Are there any left?’

‘Oh, aye, plenty.’

May stopped. It was too much. She couldn’t believe it could happen. The police, the Corporation, they said they’d help her get away and here she was about to get her new start. He’ll find me. He’ll chase me all the way to Red Road. He’ll wreck it. She didn’t deserve this, one of these immaculate houses.

The man waved his hand over the ballot box and said, ‘On you go.’

Yes, she bloody did deserve it.

Eyes closed, she put in her hand and felt for a slip of paper.

‘What have we got, what have we got?’ Her son jumped up to look at the piece of paper.

‘Fifteen/three, that’s what we’ve got,’ she said to her son.

‘Fifteen/three.’

‘Is that a good one?’

‘Oh aye, son, that’s a good one.’

‘Now, some folk have been swapping their houses if they’d prefer something higher up or lower down, and that’s fine,’ the man said.

‘Oh no. I won’t be swapping my house.’

She handed the piece of paper to the man who wrote her name and house number in a ledger and gave her a set of keys. An elderly couple leaning on sticks stood behind her. May turned around and held her keys out to them, just as the man in the suit had done to her.

‘I’ve got my house.’

‘Well done, hen, that’s smashing.’

‘On you go up in the lift,’ the man behind the desk said.

‘Which one?’

‘Either. They both go up and they both go down.’

May took her son’s hand and stood proudly by the lift, looking at the painted walls and the sparkling ceiling and floor. She tapped her fingers against his.

‘Calm down, Ma,’ her son said.

‘I can’t help it.’

The lift was full of people when the doors opened. They seemed like her kind of people, happy and friendly and the folk that squeezed in with them seemed like her kind of people too, one man taking all the orders for the floors, pressing the buttons and calling out mind the doors.

It was the cleanest, most amazing house she had ever seen, with a view out over the Broomfield. All fields and grass. Gorgeous. A bathroom inside the house with basin, toilet, bath. A kitchen with spotless cupboards, an electric cooker and oven. A living room, two bedrooms, a veranda off one of the bedrooms and another room with no windows but big enough for something – what? – she barely had anything to fill the house with. It opened out, bare and lit and freshly painted, in front of her. She would work to fill the house with furniture and rugs and crockery and toys. She would work to pay the high rent. By God, she would work. She took off her coat. Where to start? And that’s when she cried, finally, knowing they were safe.

Jim 1966

Each day as Jim passed he used to see the men at work boring the fields by Red Road. He knew something was going to happen. Each day on their way along the road to the Provan Gasworks he and his wife, who worked at the gasworks too, saw the men and noted the small developments; the ground levelled, the surplus earth pushed into heaps, the concrete mixers, diggers and cranes, the workmen’s huts, until eventually it was all steel, steel, steel. Then, Jim and his wife realised that something big was taking place, something mammoth.

Jim worked hard; the gaffer of the labouring squad at the

gasworks. When the industry moved from old coal to oil, the foreign gas, he was there, in charge of his squad. The catalyst squad. The pick and shovel days were away and it was chemicals they used now. Cleaner, safer. Jim took his job seriously.

It was his wife who said to him shall we try for a house in the Red Road Flats and because it would be handy for work, Jim said, aye, why not. The older children married or working away. Just the younger two under the roof. The bairnies.

Twenty-eight/four. Ten Red Road. A view to the west and a glimpse of the Arran hills on the clearest of days. High enough to see whole sunsets spread like syrup across the sky.

Matt Barr

I was nine when we moved there. My first memories were my dad trying to describe an electric fire. It was fitted on the wall in the living room. We came from Springburn, a room and kitchen up a close with an outside toilet on the landing. My mum and dad slept in the kitchen in a wee in-shot where there was a double bed and then you went through a lobby and there was a big front room which was like a general purpose room but we had a big double bed in it and all three brothers slept in the same bed together. It was a godsend to move to a beautiful brand-new house. I remember when we moved in they were still actually building all the other blocks and there was a big fence that ran all the way round the building site. I remember there was nothing to do, no playgrounds, no amenities. So we played in the building works a lot. We were

always getting chased by watchmen. We were quite young. We never did anything bad.

Jennifer 1966

They went for a walk. To get to know the area, her father said, and her mother spent a wee while at the mirror fixing her hair. Her father kissed her mother’s neck. Jennifer and her brother wore their chapel shoes and their granny’s knitted jumpers underneath their winter coats. Their mother tilted their faces to her and patted their heads before they left the house. The lift shook its way to the ground.

‘Where are we going?’ Jennifer said, because the day felt like an event.

‘Where the wind blows,’ her father said.

When they walked through the canopy by the foyer doors the wind did blow, swirling construction-site dust and debris at their feet. Jennifer and her mother nearly toppled and their coats flapped open to their bottom buttons. The family stepped out from the canopy where the wind was still cold but less charged.

Around them noise from the construction site was loud. They walked through frozen mud tracks and stood by the perimeter fence of the new long block and listened to the clangs and chips and thuds of the workmen inside.

‘What I would like to do is get a loaf of bread,’ Jennifer’s mother said and they looked for a shop.

‘That’s where they’ll build the shops,’ her father said.

‘No good to me at the moment.’

‘Will we walk to Springburn? Or the ones at the top of the road?’

‘We’ll have to.’

But they didn’t walk yet. Instead they looked up at the building in which they lived and their father told them to count down three rows of windows from the top. Twenty- eight, Ten Red Road Court. Flat four.

‘It hurts my neck to look,’ Jennifer said.

At the very top of the building strips of cladding met in a pinch, not quite a point, and the windows thinned to black lines.

Her father curved his hands above his eyes. ‘What an idea. The audacity of those men. Colleen, did you ever think we’d be living twenty-eight up in a brand-new multi-storey?’

‘No, I did not. If they built some shops, this place would be perfect.’

They stood, the family, in the cold wind and waved at the men and women and weans standing at other windows, eager and open and smiling.

‘Where can we play?’ Jennifer said.

Her mother and father looked about them at the workmen’s huts and cranes and scaffolding.

‘You can take a skipping rope or your balls and play outside the building,’ her mother said and although there were no swings or slides, Jennifer thought that Red Road – the half- built buildings, the fields, the dips and ditches – was the most exciting place she’d ever seen.

‘Jim, these weans will bring mud into the house every time they come in,’ Jennifer’s mother said. ‘To think I scrubbed the Possil house from top to bottom to make them let us live here.’

‘It worked. You did good. We’re here,’ Jennifer’s father said and he took his wife’s hand. ‘Handy for work, too.’

Davie 1966

He held onto the cold scaffolding and looked at the pile of sand that rose below him like a great grey wave. One more jump. The highest one yet. They’d given the night watchman the runaround then hidden until he’d walked away, thinking, perhaps, they’d finally gone to their beds. Not so, Mr Watchman. He knew his friends were waiting behind the fence with their booty – scaffolding bolts and wooden boards. He turned and gave them the A-OK finger circle and breathed in before he leapt.

It was supposed to be a silent jump, like the Commandos, but it wasn’t. He couldn’t.

‘Raaaah, oh oh oh rahhhh, ya beauty!’

He hooted and yelled and roared his beautiful drop to the sand. Sand covered him when he landed and he rolled, nothing in his ears but the scuff and rustle of his moving body, and when he lay in the sand, shoulders and head and arse half-buried, and breath coming out in laughs, he looked through the high scaffolding and felt extraordinary. The night fizzed, the clouds hung heavily.

Then he remembered the rats and sat up. Shouts.

‘Sorry Davie!’

‘Davie! Enemy!’

It was his pals, running away, the fence still jangling. Davie dragged his legs through the sand and was running to leap the fence when the night watchman’s torch dazzled him. Before he could bolt, the night watchman’s hand grabbed his arm and got him in a head hold. It hurt. He felt knuckles against his forehead.

‘Game over, son.’

Torchlight was in his eyes again. Sand in his mouth.

‘I’ll go quietly.’

‘You annoying wee prick.’

‘I was training.’

‘I’ve got a job to do.’

‘Don’t tell my da.’

‘Now that’s an idea. Right, you, out, and come with me.’ The night watchman straightened Davie up and gripped his

neck, marching him to the gate. They walked to Thirty-three Petershill Drive. Davie wondered if his friends were hiding anywhere and he did some Commando hand signals in case they were but stopped when the night watchman told him to pack it in, you bammy bastard.

Nobody about. Warm lights in some of the houses. Davie wondered what his da would say. His brothers would laugh. They’d be able to laugh in safety now, because they had their own beds, unlike the other house, with the three of them in one bed and never knowing who was going to get skelped as well when his da came in to administer discipline.

‘I’m going to leave you here and watch you get in the lift and you’re going to go in your house and get into your bed and give me some peace. If I catch you out here again I promise you, your da will know about this.’

The night watchman pushed Davie through the door. Davie pressed the button for the lift and wiped sand off his knees. He snuck a look at the watchman and saw that he was shorter than he’d thought, and younger, and he looked a bit like his uncle John. He watched him put a cigarette between his lips and light up, flicking the match to the ground.

‘On you go,’ the night watchman said through smoke, and motioned towards the lift.

Without a word Davie returned to his house.

‘Did you do the jump?’ his brother asked, lifting his head off the pillow.

‘Aye. I flew.’

‘Did you get caught?’

Davie undid the catch on the window and leaned right out.

‘No way.’

He saw the night watchman down below, patrolling the piles of sand and scaffolding with the unmade tower reaching into the dark sky, and when the night watchman was away over the other side of the site, he saw the rats come out, odd random rats at first, darting and stopping and starting, and then a whole teeming load of them, crawling over everything, getting in about it, reclaiming the place and picking at the workmen’s pieces.

Jennifer 1966

Jennifer’s mother told the children to go out or stay in but not to play on the landing. Her children chose to go, the back stairs ringing with their heavy footsteps. We want to try these stairs, they said and she shouted after them to take care and mind they didn’t bring mud into the house when they returned.

Then Jennifer’s mother propped open her front door and collected up her neighbours’ doormats and her own. She put hot water in a bucket, added some Flash and took her mop from the cupboard. Downstairs in the foyer she’d seen a sign with the number four on it which meant it was her turn for washing the floor.

Flakes of mud and faint footsteps covered the floor. There was more dust and dirt in the rectangles where the doormats had lain. She swept first with a bristled brush and tipped the sweepings down the chute. Then she ran the mop over the mud, pushing it hard over the bits that had stuck to the tiles.

The woman from number three opened her door and told her to come in for a cup of tea after, if she had time, and Colleen said she would, even though there was the tea to be cooked and she was just in from her work herself. She used fresh water to clean the suds from the floor and then she used a di

sh towel to dry the floor. And while she had the mop and bucket out she did her own floors too. Then she went next door for a cup of tea and the women stood on the veranda with their cups in their hands and the wind in their faces, looking down at the weans and the workers coming home off the buses below.

Jean McGeogh

Aye, they were all going up, they were all getting built. There was a lot of noise but it was good. I loved the flats, I loved them. Great neighbours. Neighbours in a million they were. Really all working-class folk, you know, good, honest, and you could leave your door opened and anything.

Jennifer 1967

Jennifer’s father called the family into the living room. He told them to mind the pasting table and be careful of the dust cloth. Then he cast a hand in front of the red swirls on the wall and said, ‘See this, this wallpaper. It will outlast us. Outlive us. Put up by the hands of a master decorator. It’ll be up for the next fifty years.’ Jennifer’s mother ran her palm over the wall and said, ‘It’s very red.’

‘Do you like it?’

She smiled. ‘I love it. It’s just how I wanted it.’

Jennifer liked it too. The living room looked like the pages of her mother’s magazines. Hot and red and luscious; the swirls on the walls like the swirls on her dress.

‘Away and play,’ her mother and father said at the same time. Her father put his fingers through his hair and his hair stayed spiked. Jennifer and James grabbed their coats and shut the door behind them.

Outside, they ran across the mud to where the men were building the next tower. Steel and cranes and temporary floors way up the inside of the building. They found a sheet of plastic which James stabbed at with a stick. They saw asbestos. Jennifer picked up a piece then threw it to the ground. She found a better piece, good for drawing lines, and they ran back across the mud to the side of their block. James left her and went to talk to a boy on a bike. Jennifer marked her beds on the ground and threw her peever stone. Girls came along, including the girl from number three with pigtails, Jennifer’s neighbour. They played, taking their own stones from their peever tins, bending close to the ground as they drew more beds with more asbestos.

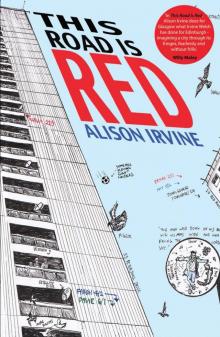

This Road is Red

This Road is Red