- Home

- Alison Irvine

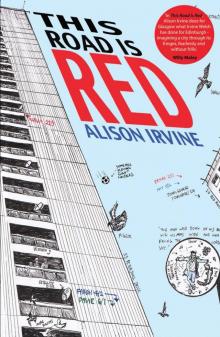

This Road is Red Page 5

This Road is Red Read online

Page 5

Down past Thirty-three block and out came Davie Kerr with his owl and his air gun and a line of weans following him.

‘All right Brendan,’ Davie shouted, the owl flapping as it sat on his gauntlet, the weans with their shoe boxes, off egg collecting, watching the bird as they walked.

‘No, I’m fucking well not,’ Brendan said and ran on. He could hear the boys counting, still. Soon they would charge at him like fucking Vikings and they would catch him and his doing would be brutal because he won the squash and got full of it. He had a right to, but.

Or he could just give up. Alfie did that once and the boys were so disappointed in him they let him off and found some- thing else to do. But Brendan had a feeling that the boys wouldn’t be satisfied today until they’d got him good and proper. He wondered when he and Ewan could be sending their Action Men out the window with their parachutes on, as that’s what he really wanted to be doing now.

The caretaker was on his veranda. Brendan ran past him and looked up. He saw the caretaker clock him and look over his head up Petershill Drive. The boys must be coming.

‘Help!’ Brendan said and regretted it.

‘Eh? What’s that, wee man? I can’t hear anything, the weans are too noisy.’

Brendan flicked him the fingers. The caretaker hated him. He could go to Jimmy’s dad’s house – he was only three up – and bang on the door, but Jimmy would just let himself in the door and they’d get him. Silently.

There was the tunnel to Germiston. It was right in front of him. He ran to within a foot of it. But he just couldn’t. There could be boys from Germiston hanging about the other end – he knew what happened when you got so far inside that tunnel; you couldn’t see in front of you and you couldn’t see behind you. Everyone was scared of the tunnel.

He heard the boys coming after him. ‘Cunt!’ they shouted. So he ran up the slope onto the grass where the football matches were going on, and for a while, he felt free of the boys charging behind him as he threaded a path between the players. As long as he didn’t get in the way of anyone’s ball he would be okay. Past the white-walled community hut where the older boys boxed. He was puffing hard and slowing down. How long had he been running for now? Five minutes? Ten minutes? Once he ran for twenty minutes before they caught him and he was so tired and his doing was so bad he might as well have lain down and taken it after the twenty second countdown. He sneaked a look behind him to see how close they were. Oh mammy daddy, the whole fucking football pitch was after him now; a great charging throng of boys running at him, glee in their faces, with mad Mark Dougan leading the charge who his pals had banned from playing Hunt the Cunt last summer because he was such a bammy bastard when he caught anyone. He thought through his options as he tugged his breath in and pushed sweat off his forehead. The railway tracks were a sprint away. If he was lucky he could tumble down the embankment and be across the tracks and maybe a train a mile long would come by and the boys wouldn’t be able to catch him. But he would be trapped over on the Gyto’s side and those bastards would give him a worse doing than his own side would. So the railway tracks were a no go.

He was too late to chase after Davie and his owl and the line of weans. He and Davie went bird-nesting together. Davie could point his air gun at them all or set his owl on them – but the wild shrieking mass of boys, and girls now too, was between him and Davie. Thirty-three Petershill Drive was the closest building. Nup. Keep out in the open where people – adults – could call a halt to the thrashing.

Brendan’s only option was the Glasgow Hire and Transport Company. He ran towards it, seeing the trucks get closer and larger. He turned round once and saw the crowd spread like the wake on the Rothesay ferry. He kept running, his legs heavy and his forehead prickling. He could hear shouts still. Ewan’s voice, ‘Give up, Cunt,’ and ‘Mark, go easy on him,’ and he knew that the fun was still very much in this particular game.

As he ran, Brendan heard a truck’s engine start up and he scanned the cabs to see which one would move. It was his only hope now and when Brendan saw a truck snake itself out of the concrete truck park towards the exit, Brendan ran like his life depended on it. Which it did. The crowd was still behind him. Some had given up the chase – fuck, he must be a good runner. Put that on the list of talents for Brendan MacDonald along with tennis and squash why don’t you Ewan Geddes. He’d done it hundreds of times before, got away with it and not got away with it, but failing was not on his mind today. Brendan sprinted for the back of the truck and leapt up for the hudgie of his life just as the truck’s engine drove its slow procession through its gears, left onto Petershill Drive and away down the road. Brendan turned. Hands grabbed at his legs. Big wide open mouths with frenzied teeth. ‘Fuck yous, you baw bags!’ he shouted, one hand cupped around his mouth, the other gripping the back of the truck, his arm taking his whole weight as he leaned out. ‘Get it right up yous!’ He swung himself straight and held on to the truck as it roared down the road. He saw a woman with a message bag walking towards the flats, he saw the postman on his bike with his bag of mail. Then he pressed his forehead to the truck’s metal back, held on tight and gave himself up to the jiggling and rumbling and jolting and jerking of his escape.

Davie 1970

The boys waited for a bus to pass and then crossed Red Road.

‘Are you sure, Davie?’

Brendan was up for most things but Davie knew he was scared of Avonspark Street.

‘I’ve got my air rifle.’

‘They’ll think we’re starting a war against the Avey Toi.’

‘No they won’t.’

They wheeled their bikes because they agreed it looked less warrior-like, but both boys had practised jumping on them in seconds in case they had to escape.

‘Which house?’

‘My ma said it might be the last one on the right.’

‘Right up the other end of the street. We’re going to get battered.’

‘No, we’re not.’

With the Red Road towers behind them, they walked. The boy’s ma opened the door. She wore glasses.

‘We’re looking for Malcolm White.’

‘Put that air gun down before you say another word.’ Davie put the gun down and laid his bike on the ground

too. He took the newspaper cutting from his pocket.

‘We’re looking for Malcolm White, the one who was trapped up the Campsie Fells, when he went nesting, it says here.’

The woman paused.

‘Malcolm, come here a wee minute.’

The three boys stood with their bikes out the front of Malcolm’s house. The boy Malcolm pumped his tires and offered the pump to Davie and Brendan. They did theirs too. Malcolm tightened a screw and wiggled his handlebars.

‘Have you seen Kes?’ Davie said.

‘I fucking love that film.’

‘I’m going to get a kestrel. I had an owl but I let it go.’

‘You got one in mind?’

‘There’s a nest on the Shovel gorge, where you...’

‘Where I fell, aye. Are they hatched?’

‘Aye. Four younks. Nearly fledged. I’m going to take the biggest one. Reckon today’s the day.’

‘I’ll help you.’

Davie and Brendan looked at each other and smiled. They set off down Avonspark Street, back the way they came, towards the flats, riding their bikes, Davie with his air rifle tucked under one arm, all three of them with shoe boxes tied above their back wheels. Malcolm’s bike had a flag on a bendy pole that came out of his seat back. Some boys came out of a house and waved at Malcolm. He waved back. His pals looked like they knew how to fight.

‘What was it like, when you were trapped up the Campsies?’ Brendan said.

‘I made a den. I was fine. It was everyone else who was worrying.’

‘Aye right.’

‘Aye fucking right.’ Malcolm’s bike skidded to a stop and

Davie remembered Malcolm’s association with the Avey Toi.

&

nbsp; ‘I’m going to keep it on my veranda,’ Davie said and

Malcolm looked away from Brendan and stared at Davie.

‘You need to get a license to keep a kestrel.’ He started pedalling again.

‘I’ve got a license.’

‘You need a garden and outdoor space.’

‘Don’t you worry, I fixed it.’

The Red Road Flats came at them blank and massive as they turned from Avonspark Street and pedalled up the hill.

‘Which building do you stay in?’

‘Thirty-three Petershill Drive. The one behind us.’

‘It’s like space, watching you at night. You look like rockets, all of yous.’

‘We watch you too,’ Davie said. ‘The car chases and the fights.’ The chat quietened down as they cycled hard.

Past Stobhill Hospital, through Bishopbriggs, on to Milton of Campsie on their precious bikes, parts swapped or stolen then fitted tenderly. Tyres made do, bells screwed on and thumbed to test. Seats patched with parcel tape.

‘What’s your best egg?’ Malcolm said.

Davie thought. He wanted to impress the boy from Avonspark Street but he didn’t want to get found out. ‘Heron,’ he said. Which was true.

‘I’ve only just started nesting,’ Brendan said. ‘My best one’s a blue tit.’

‘Mine’s a buzzard,’ Malcolm said.

Davie and Brendan glanced at him respectfully then hunched their shoulders over their handlebars and pedalled on.

Wheeling into the Campsie Fells. Yellow tufts of grass, piebald stones, rabbits hopping about, a bothy, trees beckoning at the edges of the grassland. Paradise. The biggest playground, all theirs, no cunt in sight. And treasure to find. Species to look up in books back at the library. A kestrel to catch. The boys hid their bikes and tumbled through the grass. Halfway up a hill they stopped to look back on Springburn and Barmulloch but other hills were in the way and they saw nothing but grass and open air.

‘What was it like, really, when you fell down the cliff?’ Davie asked Malcolm when Brendan was up a tree.

Malcolm picked the bark off a stick. ‘I swore on my mother’s life I’d never steal another egg, I’d never steal another part for my bike, I’d be good for my ma, if only somebody would rescue me.’

Davie nodded.

‘Was your leg broke?’

‘Aye.’

‘Did you think you were going to die?’

‘I don’t know. I didn’t know if it would ever end.’

‘Were you frightened?’

The boys looked around them at the Campsie Fells.

‘Aye, it was scary.’

Brendan climbed down the tree and sat on a branch just above their heads. He passed down an egg and when Davie had it softly in his palm, Brendan jumped from the branch and joined them. The egg was still warm; delicate as a bubble of air, a precious thing.

‘Song thrush,’ Davie said.

‘Wrap it,’ Malcolm said. ‘You keep it. You found it.’

So Brendan found the first egg, wrapped it carefully in a leaf, and walked the slowest from that point on, his shoebox held in front of him like some gift for a king as they went on the hunt for more. They would blow the eggs later.

After a day roaming the Fells they went to the nest with the kestrel chicks.

Lights in Stobhill Hospital shone from every window. A streaky sky. Cool grey roads. The boys rode gently with hands squeezed around brakes. They stayed on the footpaths and slowed for ladies with message bags. A bus trundled ahead of them, going steady, nobody at the stops it passed. Davie saw the backs of heads on the top deck and the bottom deck.

‘Will you get a doing off your ma?’ Brendan said to

Malcolm. ‘Because it’s nearly dark.’

‘She’s working tonight. I’m going to stop at my pal’s and swap my bell for his puncture repair kit.’

Malcolm’s tyre was on its way to flat again and his chain kept falling off.

They cycled in silence to the junction of Broomfield Road. The owner of Welshies was shutting up shop, a few people stood beside the chip van, the bus indicated left for the stop at the bottom of Red Road.

Davie didn’t know how to end the day with Malcolm. He

wanted to go bird-nesting with him again. He wanted to meet this pal of his who collected eggs too.

‘Anytime you want to see my kestrel, just come up.’

‘Aye, will do.’

Malcolm nodded and the boys put their feet to their pedals.

‘Oh fuck,’ Malcolm said and stared down the road.

From Avonspark Street, a mass of men with swords and sticks and bottles ran onto Red Road. No noise, just the shape of them all, bent and charging, weapons held from raised arms. The men ran towards the bus and two men jumped off the bus and ran into the Red Road Flats. A couple of the Avonspark Street guys chased the fleeing men but most of the guys surrounded the bus. A window was smashed. Shouts and screams and women’s voices. The bus rocked as the men got on and God, it was like a cartoon, seeing the men cracking their weapons onto the men on the top deck at the back, the cowering shapes of them through the back window, the men with the weapons doing their violence over and over. And then coming off the bus in single file, stepping off and shaking themselves, as if returning from having a piss, checking the road up and down and then crossing back to Avonspark Street, thriftily, edgily, swiftly. Job done. The bus driver started the engine, the lights in the bus flashed on and then the bus was away, turning right down Petershill Drive.

‘I don’t know what that was about,’ Malcolm said. He seemed as if he was trying to shift the shock from his face.

‘No, me neither,’ Davie said.

‘I’m getting my eggs home,’ Brendan said.

‘Yeah, you look after they eggs and that kestrel,’ said

Malcolm.

The boys cycled slowly. Davie wanted to ask Malcolm if he would be all right, going the same way as the men who did the beating, but he supposed Malcolm knew them; they might be his brothers or his brothers’ friends and if they weren’t, it didn’t

matter, because they would know him because he lived there and he was from their side.

He prayed that his kestrel – he’d named him Kes like the kestrel in the film – would be okay on the veranda. From Falcons and Falconry by Frank Illingworth he’d learned what type of perch the hawk needed and how to build it. There was another book he’d ordered from the posh bookshop in town but he needed to wait a while longer before the shopkeeper gave up on him returning for it and put it on the bookshelves. Then Davie would go back and steal it.

Jesses round the kestrel’s ankles. A leash attached and tied to the perch. Food; bits of chopped mouse he’d shot over on the High Chaparral. Just the right amount of food to keep it calm but ensure it was hungry enough to man. The noise of men returning home from the bars and clubs in town worried him though. You wouldn’t get that sort of noise in the Campsie Fells. The bird would probably be frightened. Davie wanted morning to come so he could get up and take care of it.

‘Get to sleep,’ his brother said.

‘How did you know I was awake?’

‘You’re wriggling.’

‘I can’t help it.’

‘Thinking about birds.’ His brother laughed and turned over. Davie lay for a few more minutes and got up when he heard a key in the lock. He was relieved to have something else to think about. His older brother stood in the dark kitchen, washing his hands in the sink. Davie tripped over his hold-all.

‘You scared the shite out of me,’ his brother said.

‘Is that a new suit?’

‘Do you like it?’ His brother turned on the light and the fluorescent bulb flickered above the immaculate kitchen sur- faces. ‘I got it from Gerald’s. First time I wore it tonight and it’s been a success.’

‘I got my kestrel.’

‘You never.’

‘I’ll show you.’

Davie took his brother to the ve

randa and they walked the few cold steps to where Davie had set up the perch.

‘Fuck, it’s awake,’ his brother said.

The chick’s eyes were open and alert and sharp and it watched Davie and his brother.

‘Go to sleep, Kes,’ Davie said.

‘You haven’t called it Kes?’

‘What’s wrong with that?’

‘You couldn’t think of your own name?’

‘I didn’t want to.’

‘You should have called it Gringo. Or Big Baws.’

His brother touched the kestrel with the back of a finger and then took his hand back.

‘You’re a hard wee fucker, aren’t you?’

The view from the veranda wasn’t a good one. They were too low to see much other than the back of Sixty-three Petershill Drive and the tops of the swings in the kids’ playground below. Davie wished they were higher up so that Kes could see hills or at least more sky or other birds.

His big brother leaned against the railing and they watched two men walk along the path below them, bottles clinking in bags, murmuring as they walked.

‘There was an ambush on the bus earlier,’ Davie said.

His brother turned his head and spoke sharply. ‘How do you know?’

‘We were coming down the road on our bikes. The Avey Toi, they charged across the street and got the bus, smashing it up. They gave someone a right doing. We saw.’

‘Aye, I heard they stabbed a fella.’

‘Why?’

His brother lit a cigarette and threw the match over the

veranda. ‘Something to do with a score to settle. Gang members from another area. I heard it was vicious.’

‘It was like a war, I’m telling you. An ambush.’

‘Just don’t you be in the wrong place at the wrong time, all right.’

Davie decided not to tell his brother about Malcolm from

Avonspark Street.

‘Come on.’

They closed the door on the kestrel and Davie watched his brother empty change and bus tickets from his trouser pockets. He often compared lives with Billy Casper from the film and wished he could meet him in the countryside one day and say to him you’ll never guess what I saw or what my brother said or done, because he had a feeling he and Billy Casper would get along well.

This Road is Red

This Road is Red